File:

<strepsiptera.htm> < (Entomology),

(Invertebrates), (General

Index)> <Invertebrate Bibliography> <Glossary> <Site Description>

< Home>

|

An Introduction To

The Study of Invertebrate Zoology 1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Hexapoda: Class: Insecta: Order: Strepsiptera (Contact)

Please CLICK on underlined

categories to view and on included illustrations to enlarge: Depress Ctrl/F to search for subject matter:

General Summary of Strepsiptera The Strepsiptera

-- <Adults> & <Juveniles>

-- These insects are characterized by some remarkable biological phenomena.

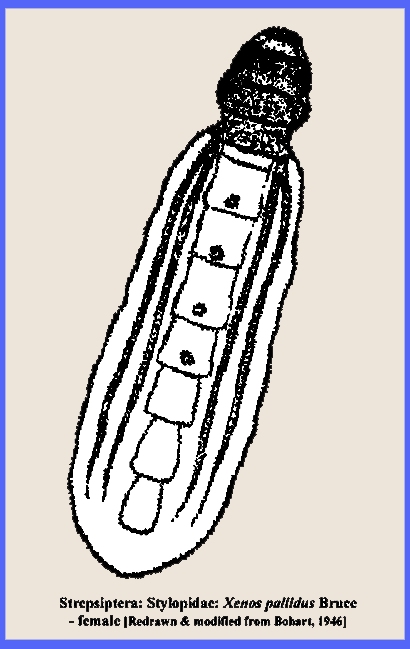

Their parasitic activity is limited to the growth stages and the adult

female. The adult males are free

living. There is marked sexual dimorphism where the females are prothetelous,

ie., their larva has a body form while they are sexually mature, and they are

all wingless. The eggs may also be polyembryonic. As many as 40 embryos

developing from a single egg, e.g. Halictoxenus parasitic on Halictus

simplex (Hymenoptera). They are usually described as having a type of

hypermetamorphic life cycle in which two larval types exist according as the

development is to be towards a male or female adult. The hosts to which their

parasitic attentions are directed appear to be restricted to the Hymenoptera

(Vespoidea and Apoidea), the Rhynchota (Homoptera), and, in one rare instance

the Orthoptera (Borradaile & Potts,

1958). Among the hymenopterous hosts the

solitary bee Andrena is parasitized

by Stylops. The female is entirely endoparasitic in the host bee, and

appears as a hernia-like extrusion from between the tergites of adjacent

segments as in Polistes. The body of that female is legless and

wingless and composed of a subtriangular unsegmented cephalothorax and a

clearly 10-segmented abdomen. It lies in the host so that the cephalothorax

is visible. Behind the mouth ventrally is a transverse slit which leads into

a brood chamber found under the cuticle of the first five or six abdominal

segments. Genital pores communicate between the internal genital system and

the brood chamber. It is through the

transverse slit on the cephalothorax that copulation with the male occurs. By

way of it, too, are born the first-formed triungulin larvae, the

female being viviparous (Borradaile & Potts,

1958)..

If the resultant individual is a

male, pupation occurs in the host after the head region has projected from

between two abdominal segments of the bee. The casting of the pupal skin

releases the male that flies away to seek a young endoparasitic female on

another bee.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Order:

Strepsiptera Kirby Family: Protoxenidae Pohl et al. (fossil record only). -- A male specimen of a

new strepsipteran genus and species (Protoxenos janzeni gen. et sp.

nov.) and family (Protoxenidae fam. nov.) was found in Baltic amber. It shows

features that seem more plesiomorphic than in living strepsipterans, such as laterally

inserted 8-segments antennae, very strong mandibles with a broad base, a well

developed galea, a short, and a transverse metapostnotum. The hindwings are feebly extended. The

abdominal tergites and sternites are lightly sclerotized. Based on a cladistic

analysis of 46 characters of males of 11 genera and three outgroup taxa, P. janzeni

is the sister group of all other known strepsipterans, and Mengea the

sister group of Strepsiptera s.s. Eoxenos is the sister group

of the remaining extant strepsipterans and Mengenillidae. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family: Cretostylopidae Kathirithamby

& Engel (fossil record only). --

A male Mesozoic strepsipteran was found in mid-Cretaceous

(Cenomanian) amber from northern Myanmar. Phthanoxenos nervosus Engel and

Huang, gen. et sp. nov., was distinguished from other species, particularly Cretostylops engeli Grimaldi and

Kathirithamby, also in Burmese amber.

Protoxenos janzeni Pohl et al. was found in mid-Eocene Baltic amber, and

assigned to a new family, Phthanoxenidae Engel and Huang, fam. nov. Phthanoxenos has characteristics

of a more primitive phylogenetic position than Cretostylopidae but still more

derived than Protoxenidae. Because Cretostylopidae

and Phthanoxenidae are not the basalmost branches of the Strepsiptera, the

history of the order must extend farther into the Cretaceous and even into

the Jurassic (Grimaldi and Engel, 2005, Grimaldi et al., 2005). The family Cretostylopidae Kathirithamby and Engel

was erected to accommodate the mid-Cretaceous species Cretostylops engeli

(Kathirithamby, & Engel

2014)

Illustrations

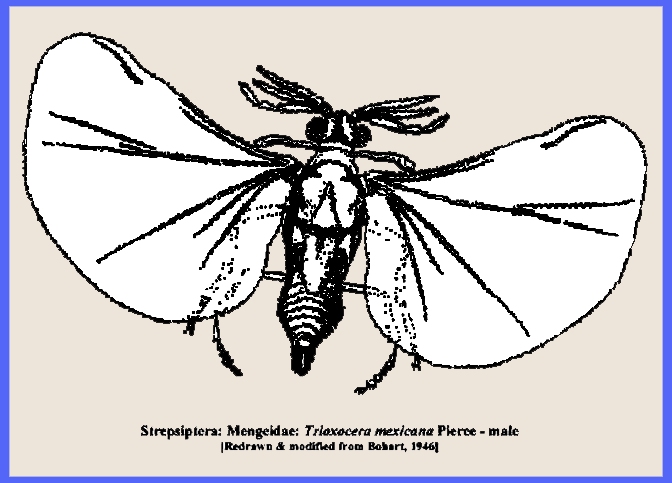

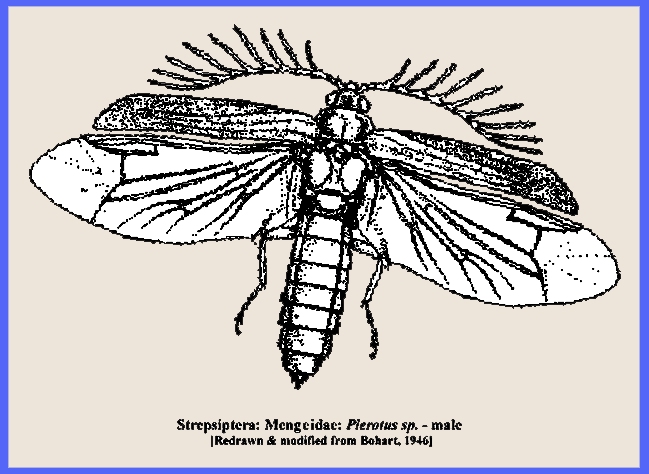

being sought - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Suborder Mengenillidia Kinzelbach Family: Mengeidae Pierce (fossil record only). -- Triozocera mexicana Pierce was

found to be parasitic on Pangaeus bilincatus (Say) (Hemiptera: Cydnidae). First descriptions and

illustrations of adult female T. mexicana are given, along with new distribution records. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Family: Bahiaxenidae Bravo et al. --

Bahiaxenos relictus is the sole member of the family

Bahiaxenidae, a type of winged insect. It was only discovered and described

in 2009 from relictual sand dunes associated

with the Rio São Francisco in Bahia, Brazil. It is considered to be the most basal living member of

the order Strepsiptera, so is the sister taxon to the remaining extant species. It is known from only a single male specimen, and its

biology is unknown. An adult male of

a newly discovered strepsipteran species from Brazil—Bahiaxenos relictus—is

described. A new family Bahiaxenidae is suggested based on cladistic analyses

of comprehensive morphological data sets with a broad taxon sampling

including the stem group. It is unambiguously placed as the sister group of

all other extant families of Strepsiptera. Bahiaxenos relictus is the

only species of basal, i.e. non‐stylopidian, Strepsiptera occurring in

the New World. It appears to be a relict taxon that has survived in the

fossil sand dunes of the São Francisco River (Bahia State). The loss of the 8th

antennomere and the greatly reduced labrum are autapomorphies of Strepsiptera

s.s. excluding Bahiaxenidae. The sister group relationship

between†Protoxenidae and the remaining Strepsiptera, and between †Cretostylops

and a clade comprising †Mengea and Strepsiptera s.s., is

confirmed, as is the monophyly of Stylopidia and Stylopiformia.

Illustrations

being sought - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family: Mengenillidae Hofeneder-- The thorax of Mengenilla was examined

using traditional morphological techniques and its features were documented

in detail using scanning electron microscopy and computer-based 3D

reconstructions. The results were compared to conditions found in other

holometabolan insects. The implications for the systematic placement of

Strepsiptera are discussed. The observations are interpreted in the light of

the recently confirmed sistergroup relationship between Strepsiptera and

Coleoptera (Coleopterida). The synapomorphies of the thorax of Strepsiptera

and Coleoptera are partly related with posteromotorism (e.g., increased size

of the metathorax), partly with a decreased intrathoracic flexibility (e.g.,

a fused pronotum and propleurum), and partly independent from these two

character complexes (e.g., not connected profurca and propleuron).

Strepsiptera are more derived than Coleoptera in some thoracic features

(e.g., extremely enlarged metathorax) but have also preserved some

plesiomorphic conditions (e.g., tegulae in both pterothoracic segments). All

potential apomorphies of Mecopterida are missing in Strepsiptera. The last

common ancestor of Coleopterida had already acquired posteromotorism but the

wings were still largely unmodified. Several reductions in the mesothorax

likely occurred independently. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Suborder:

Stylopidia Kinzelbach Family: Corioxenidae Kinzelbach (+1 fossil species) . -- The species in this family are parasites of Heteroptera including the Cydnidae, Coreidae, Pentatomidae, Scutelleridae, and Lygaeidae. Males do not have

mandibles. Three recognized subfamilies are separated using morphology of the

males, mainly on the basis of the number of tarsal segments and the presence

of tarsal claws. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Infraorder: Stylopiformia Kinzelbach

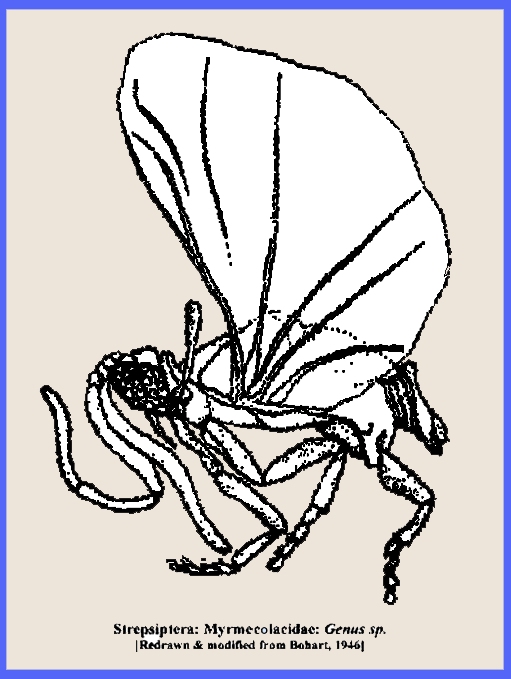

Family: Myrmecolacidae Saunders (+13 fossil species) (Stichotrematidae = Synonym) ). -- There are four genera and about 98 species in

this family. Like all strepsipterans,

they develop as parasites with males parasitizing ants while the females

develop inside Orthoptera. The sexes

differ markedly in morphology so it is difficult to match females to males in

museum specimens. Five new myrmecolacid species (Lychnocolax drysdalensis,

L. maxillaris, Myrmecolax blfurcatus, Stichotremba kuranda

and S. webbiense) were described from Australia. There are also five species described from

Malaysia, New Guinea, the Philippines and Australia. Separate keys exist to the genera of

Myrmecolacidae and to the Australian species. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Family: Lychnocolacidae Kathirithambry & Engel?. -- In a phylogenetic study of the insect order Strepsiptera, the

peculiar paleotropical genus Lychnocolax Bohart, 1951 was recovered

as the sister group to Stylopidae + Xenidae.

Bohart maintains that the correct placement of the genus is with

Mymercolacidae and a new family name is not required. Kathirithamby & Engel (2014) did base

the name on an available type genus and included diagnostic characters to differentiate the family from

other groups, but they did not explicitly indicate the name as new (since they erroneously attributed the family name

to Bohart), nor did they specifically note the type genus (even if it was apparent from the formation of the

familial name). This nomenclatural

oversight is corrected utilizing the diagnostic traits outlined in the key of

Kathirithamby & Engel (2014). - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

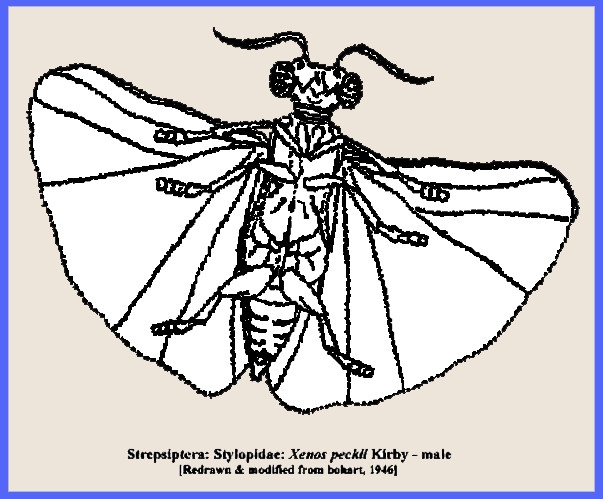

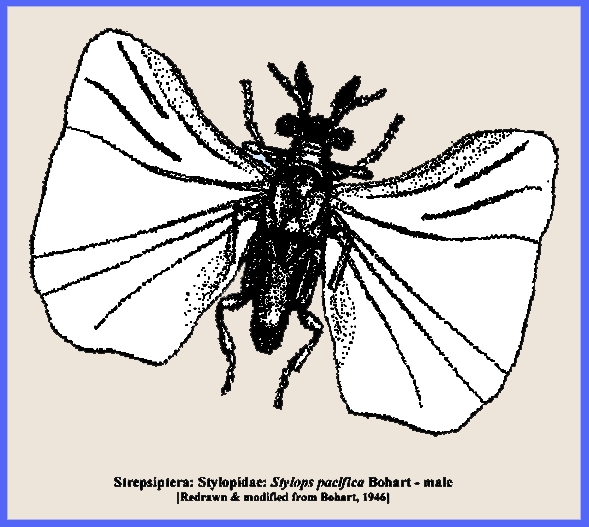

Family: Stylopidae Kirby (+2 fossil

species)

. -- Stylopidae

is a family of strepsipterans with about

15 genera and more than 330 described species. They are all parasitic

insects. Affected host insects of

this family are noted as being "stylopized". - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family: Xenidae Saunders. -- The mature insects of this family have unusually large eyes, which

is not unexpected for a group with a complex life cycle. For the Strepsiptera that are believed to

have evolved nocturnally there is little information about their

photoreceptors. Some research has

shown great sensitivity to ultra violet and green light, suggesting the

presence of color vision. This might

aid males of at least one species, Xenos peckii, to find females,

which are hidden in the nests of their wasp hosts. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family:

Bohartillidae Kinzelbach (+3 fossil species) .-- Kinzelbach (1969) described the first

species in this new genus, Bohartilla megalognatha from Honduras.

Kathirithamby & Grimaldi (1993) identified this genus in medium yellow

Dominican amber: one male is morphologically indistinguishable from B.

megalognatha, one male matches in several details the extant species and

was named B. kinzelbachi. However, Pohl & Kinzelbach (1995)

synonymised the B. megalognatha from the amber to B.

joachimscheveni described by Kinzelbach & Pohl (1994) from Dominican

amber. The only differences stated by Kinzelbach & Pohl (1994) of B.

megalognatha from the amber from the extant B. megalognatha

are: slender antennae, maxillae and longer legs; longer maxillary palpus. In

other characters the amber specimen generally agrees with those of the extant

species. Kinzelbach & Pohl also state that "as in most other

specimens from the Dominican amber, there are almost no differences from

living representatives at the species level". Kathirithamby &

Grimaldi would like to reinstate B. megalognatha from the Dominican

amber. Another new species from the amber, B. kinzelbachi, was

described by Kathirithamby & Grimaldi (1993), and the length of the basal

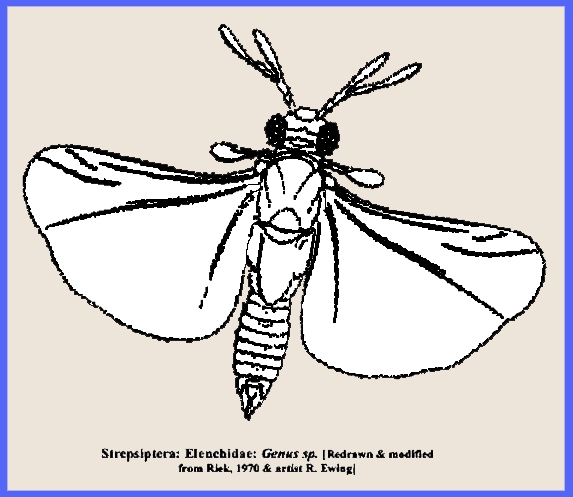

maxillary segment of this specimen is 1.5x that of apical palpi. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family: Elenchidae Perkins (+1 fossil)

. -- Elenchus japonicus a parasitoid of the

rice planthoppers Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) and Sogatella furcifera

(Horváth) in Southeast Asia (IN; Proceedings of the 8th International

Auchenorrhyncha Congress, Delphi, Greece, 9th -13th August, pg. 64.

Kathirithamby, J. 1993b.) Another

strepsipteran parasitoid Elenchus sp.

parasitizes N. lugens in Malaysia. S canning electron microscope

studies indicate that the parasitoid resembles E. tenvicornis. The free-living male of Elenchus

sp. emerges both from 5th instar nymphs and adults of N. lugens. The neotenic female Elenchus

sp. emerges only from adult hosts. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Family: Halictophagidae. -- Coriophagus hansoni n. sp.

is the first in that genus from Central America and the second Coriophagus

species from the New World. Halictophagus

crasiartus n. sp. is the second species described from Costa Rica in this

genus and the third in Central America. A

new species of Halictophagidae (Insecta: Strepsiptera), Halictophagus

forthoodiensis Kathirith- amby & Taylor, is described from Texas,

USA. We also present a key to 5 families, and a check-list of 11 genera and

84 species of Strepsiptera known from USA and Canada. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Family: Callipharixenidae. -- Callipharixenos muiri Pierce is parasitic in

Calliphara billardierei F. (Heteroptera) from

Cambodia, and C. siamensis Pierce is parasitic in Chrysocoris

grandis Thunberg (Heteroptera) from Cambodia and Thailand (Pierce

1918). Only females and first instar larvae of this family are known.

Their synapomorphies with the higher Stylopidia are: a flattened

cephalothorax, two pairs of functional meso- and metathoracic spiracles and

five genital openings (Kinzelbach

1971). Until males of this species

are found it would be difficult to determine the phylogenetic relationship

with other families of Stylopidia. Males

are unknown - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - All Strepsiptera, which were first known as Stylopids,

are parasitic on certain adult insects.

Members of this order were frequently incorporated into the Coleoptera

as a superfamily: Stylopoidea. The males have twisted wings, and the front wing is

reduced to a halter while the hind wing is very elongated and pleated. Females are apterous. Mouthparts are vestigial and nutrients

enter by diffusion from the host. The

male is the free-living active form, while the female spends her entire life

in the abdomen of a host insect. Eggs

hatch and triangulin larvae emerge.

As the parasite larvae mature the female form remains indistinct with

little more than a head, which protrudes from the host segments. The male does leave the host,

however. Insemination of the female occurs on the host. Genitalia of the female are on the cervix

region. After impregnation the female

simply turns into a bundle of eggs.

These egg hatch, releasing triungulin larvae en masse, which then

escape through the body wall of the host.

They seek out a new host by perching on flowers, etc., or wherever

another insect (e.g., bee) might alight. ------------------------------------------- Details of Insect Taxonomic Groups Examples of beneficial species

occur in almost every insect order, and considerable information on

morphology and habits has been assembled.

Therefore, the principal groups of insect parasitoids and predators

provide details that refer to the entire class Insecta. These details are available at <taxnames.htm>. ============== Bravo, F., H.

Pohl, A. Silva-Neto, and R. G. Beutel. 2009. Bahiaxenidae, a ‘‘living

fossil’’ and a new family of Strepsiptera (Hexapoda) discovered in Brazil.

Cladistics 25(6):614–623. Grimaldi, D.,

and M. S. Engel. 2005. Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK. xv+755 pp. Grimaldi, D., J.

Kathirithamby, and V. Schawaroch. 2005. Strepsiptera and triungula in

Cretaceous amber. Insect Systematics and Evolution 36(1):1–20. Hu¨ nefield, F.,

H. Pohl, B. Wipfler, F. Beckmann, and R. G. Beutel. 2011. The male

postabdomen and genital apparatus of Mengea tertiaria, a strepsipteran amber

fossil (Insecta). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research

49(4):298–308. Kathirithamby,

J. & M. S. Engel. 2014. A revised key to the living and fossil

families of Strepsiptera, with the description of a new family,

Cretostylopidae. J. Kansas Ent. Soc.

87(4): 385-388. Kinzelbach, R.

K. 1979. Das erste neotropische Fossil der Fa¨cherflu¨ gler (Stuttgarter

Bernsteinsammlung:Insecta, Strepsiptera). Stuttgarter Beitra¨ge zur

Naturkunde, Serie B (Geologie und Pala¨ontologie)53:1–14. McMahon, D. P.,

A. Hayward, and J. Kathirithamby. 2011. The first molecular phylogeny of

Strepsiptera (Insecta) reveals an early burst of molecular evolution

correlated with the transition to endoparasitism. PLoS ONE 6:e21206 [1–10]. Pohl, H., and R.

G. Beutel. 2005. The phylogeny of Strepsiptera (Hexapoda). Cladistics

21(4):328–374. Pohl, H., R. G. Beutel, and R. Kinzelbach. 2005. Protoxenidae

fam. nov. (Insecta, Strepsiptera) from Baltic amber – a ‘missing link’ in

strepsipteran phylogeny. Zoologica Scripta 34(1):57–69.

|